The Empowering Legacy of Madhubani Art

Ragini Jha

Originally featured in the @brownhistory newsletter.

When travellers arrive at Madhubani Station in Bihar, they are greeted by walls covered with stories: community celebrations, romantic unions, women gathering to share wisdom. This display of artistic storytelling, created by nearly 200 local artists, goes beyond preserving tradition; it amplifies women's voices, and challenges the misrepresentations that have obscured the depth of Bihar's cultural history.

Teeming with untold stories and artistic traditions, Bihar’s identity as the Land of Enlightenment remains largely unknown. When I tell people my family is Maithil or Bihari, reactions range from a complete lack of recognition to an upsetting dismissal. At best, people ask to be reminded where it is, and at worst, they associate the state with stereotypes about violence and a lack of education. Media portrayals have done little to challenge such misconceptions, with many actors doing exaggerated Bihari accents in movies about people who wield guns and dance in gamchas on the street. Anti-Bihari sentiment continues to be prevalent in India, and this not only weakens national social cohesion, but also undermines the significance of Bihar’s contribution to India’s artistic history.

One overlooked tradition is Madhubani, or Mithila painting, one of the only art forms in the world which is predominantly practised by women and is focused on women’s experiences. Madhubani paintings have been challenging patriarchal norms for centuries, yet remain relatively unknown beyond their birthplace. Interestingly, Madhubani’s signature patterns and colours are probably familiar to many people, and can be seen on various mediums such as textiles and home decor. However, the art form’s deep-rooted connection to Bihar, feminism, and storytelling often go unacknowledged.

Mithila is said to be the birthplace of Princess Sita, and legend has it that Madhubani painting was born when her father brought artists from all over the region to depict her wedding to Lord Rama. The art was displayed all over Mithila, and inspired women to tell their own stories through these paintings. To this day, Madhubani artists often use the same natural pigments as their ancestors from centuries ago, made from fruit, flowers, haldi, and rice paste. These not only add a unique texture to the art, but also allow women to pass down traditions and artistic practices across generations.

Beyond its contribution to preserving folklore and local histories, Madhubani art plays a vital role in community building. In many Bihari villages, Madhubani painting is a collective endeavour which brings women together to create large-scale murals, covering the walls of communal spaces, temples, and public buildings. The artistic process itself becomes a platform for intergenerational knowledge exchange, mentorship, and skill development. Mothers, chosen family members, and mentors empower each other and foster a sense of shared purpose and cultural pride.

At the heart of Madhubani art is its use of symbolism. From geometric patterns to nature-inspired motifs, each element holds cultural significance. The lotus, for example, symbolises knowledge, growth, and the divine feminine. Birds are used to show companionship and love, while the sun and moon symbolise light, warmth, and the circle of life. By using these symbols in storytelling, Madhubani uniquely celebrates the experiences and qualities associated with womanhood. Passed down through generations, traditional stories are intertwined with the artist's personal experiences, often reflecting the joys, struggles, and aspirations women have.

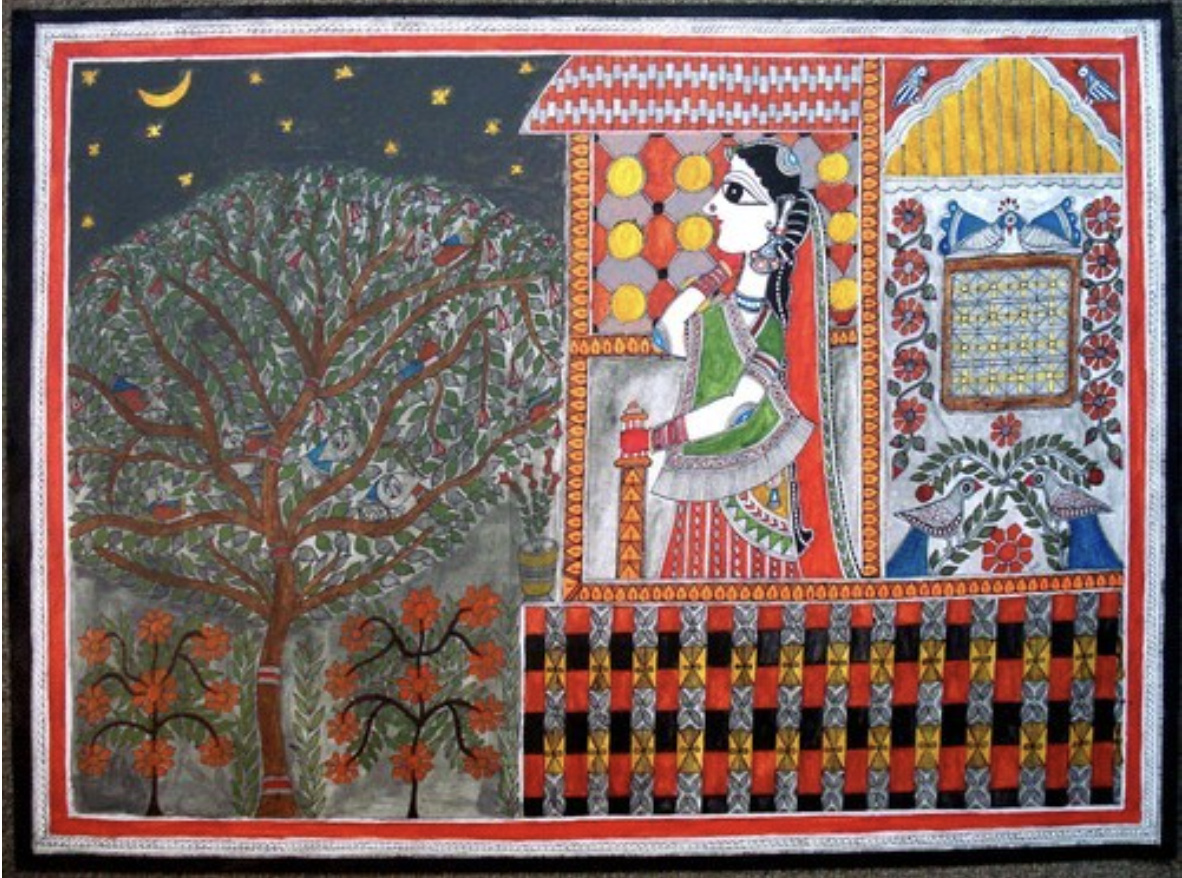

Gazing at the Moon, Rani Jha

Two Women, Rani Jha

Rani Jha’s Gazing at the Moon, for example, depicts a woman reflecting on her lack of freedom. As she looks towards the night sky, the moon signifies a sense of longing and self-exploration. Although the woman looks wealthy and well-dressed, the painting shows a stark contrast between the limitless sky and her emotional and physical confinement. In Two Women, the same artist shows intimacy between friends and the closeness they feel far from society. They are shown talking in what looks like a cocoon, which symbolises the way they protect each other emotionally and physically.

Flooded Villagers while Officials Chat, Angeli Kumari

The new generation of Madhubani artists are addressing social taboos like never before. Although this art form has always been a way to empower women, it is recently being used as a platform for social commentary on relevant political issues such as reproductive laws, gender fluidity, corruption, and more. In Angeli Kumari’s Flooded Villagers while Officials Chat, villagers are depicted struggling to escape flooded streets while men in uniforms talk in an office. The painting can be interpreted as a critique of bureaucratic inefficiency and systemic negligence. The juxtaposition of the villagers' predicament with the composed conversation among the officials highlights the disconnect between those in power and the marginalised communities they are meant to serve.

More recently, Madhubani has also been a way for historically marginalised groups to commit their unique histories to canvas. Artists such as Yamuna Devi, the first Dalit Mithila artist to receive the National Award and gain international recognition, assert their identities and challenge the social hierarchy that exists to this day. Many groups are able to use this art form to illustrate the struggles and aspirations of their communities, as well as challenge dominant narratives and confront deep-seated prejudices.

In this way, Madhubani art combines social activism and storytelling, often including a deeper exploration of the feminine experience. Madhubani paintings capture a spectrum of diverse narratives, from goddesses in epics to social issues and everyday moments. For decades, these paintings have reflected concerns that impact the artists’ communities, and have the power to initiate conversations and create community engagement. Furthermore, many women artists have been able to gain financial independence through selling their paintings and play a vital role in boosting Bihar’s economic growth.

In an effort to boost this growth, the government of India launched the “Make in India” campaign in 2014 to promote local goods and services, and although there was international investment in this campaign, folk artists were unable to benefit, sometimes making less than 2000 rupees (USD 25) for a painting which took a month to create. The pandemic also took a major toll on this growth, and despite police officers and politicians donning hand painted masks to support local artists, it was incredibly difficult for women to sell their products. Many of them experienced delays in payment, couldn’t access necessary supplies, and struggled to advertise.

In a continued effort to recognise these women, Madhubani hosts an annual Mahotsav which not only showcases folk traditions, but also provides opportunities for local artists. This festival attracts tourists from both within and outside of India, and replications are done in every corner of the world. Visitors are treated to colourful exhibitions and stalls where they can observe Madhubani artists at work and purchase hand painted sarees, pottery, and more. Family incomes depend on these festivals, but they are too few and far between to make a significant financial contribution. Year-round opportunities exist in markets like Dilli Haat, but getting the shipments to bigger cities can be an ordeal in itself.

This ordeal is further compounded by cultural appropriation and “partnerships” between Western brands and folk artists, where brands charge hundreds of dollars for hand painted products while providing meagre compensation to the artists involved. This manipulation has been occurring since 1929, when W.G. Archer “discovered” Madhubani art, and imposed casteist, sexist meanings on the murals he saw. Instead of engaging in discussions with the women who created the paintings, Archer relied on his Cambridge University background and drew connections to popular Freudian theories and Western notions of sexuality. His wife, Mildred, also wrote an error-filled book which furthered this distortion of Madhubani art, and her influence extended not only to Western audiences but also to various regions within India.

Today, many Madhubani-inspired products are commercialised and mass produced without the involvement or consent of the original artists. This commodification can result in the distortion or oversimplification of Madhubani motifs and styles, turning them into mere decorative elements divorced from their cultural significance. Several Western brands have appropriated folk art and South Asian script with little consequence. Just this week, Zara released a shirt that says “chawal - dilli ki dhoop, dilli” in Hindi script, which translates to “rice - Delhi’s sun, Delhi”. Urban Outfitters is another infamous illustration of this issue, and while they have recently started acknowledging the artistic style of their products, there remains a glaring absence of recognition for the original artists or the specific region from which the art originates.

Joy of Living, Pushpa Kumari

Geometric patterns inspired by signature Madhubani styles can be found everywhere from Anthropologie to Lakme Fashion Week. More recently, these motifs and storytelling elements can also be seen on luxury home decor, and have been adapted to tapestries, cushions, and table linens. There are several examples of ethical partnerships between modern brands and folk artists. In 2022, Pushpa Kumari was the only Indian artist to be featured on JCDecaux bus shelters in New York, Chicago, and Boston. She used this platform to display her Madhubani painting, The Joy of Living, which brought awareness about the importance of vaccinations. Although this is an incredible step for awareness of Indian folk art, women in rural Indian communities cannot gain financial independence or true recognition until Madhubani’s legacy is properly acknowledged.

This can only be achieved by addressing the deep-rooted issues that have so far hindered the advancement of this art form. The feminist narrative embedded in Madhubani paintings must be appreciated, as well folk artists’ contribution to India’s cultural heritage. Moreover, combatting the pervasive anti-Bihari sentiment is crucial. This bias, fueled by stereotypes in popular culture, has hindered the economic and social progress of Bihar and its artists. Education plays a pivotal role in this awareness and appreciation. Academic institutions can contribute to honouring folk artists by integrating their history into their curriculum.

Digital platforms and social media allow Madhubani artists to showcase their work to a global audience, reaching potential buyers who may not have otherwise been exposed to their work. Artists can now create online portfolios, share their creative process, and engage with communities all over the world. It is through genuine support, fair compensation, and an unwavering commitment to cultural preservation that these women can truly achieve financial independence and the recognition they deserve.